News:

My short story, “Tasmanian Shores,” originally published in Prairie Fire, is now available to read on my website.

My new short story collection, Rubble Children, comes out in July! Keep your eyes out for launch and reading event dates.

The genocide in Gaza is approaching its eighth horrible month. If you’re at all able, donate to a gofundme, or to the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund.

Last fall, Steph’s work friend heard that Alice Munro had died, brought the news home. I’m not one to usually react to a famous person’s death, but something immediately welled up in me. I checked the internet constantly, waiting for the news to break, but it never did. “It looks like Alice Munro didn’t die,” I said a week later. “I guess not,” Steph said.

A small reprieve, then: more time to read and think about her work while knowing she was out there, somewhere, in that place known as southern Ontario, on the Saanich Peninsula. Retired, yes, but still sharing the planet with me, with us.

Like nearly everything in my reading life, I feel like I came to Munro late. But now, she’ll be there forever. The floating shelf above my desk is reserved for the two authors that currently mean the most to me: Munro and Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve always thought of Le Guin as Munro in space, but the reverse holds some truth as well: Munro as Le Guin on the shores of Lake Huron. There are the obvious similarities: both white women born in the first half of the twentieth century; both commercially and critically successful; both writing about the promise and pain, the need and the fear, of feminism. The deeper, harder-to-elucidate likenesses: their preoccupation with time, with space, with distance. Their sentences. Their ability to dive into the beating heart of a single life, pull back to the flowing rivers of the cosmos. In both published oeuvres, a lifetime worth of discovery.

I’ve included a Munro story in every fiction workshop I’ve ever taught. In the fall, it was “Simon’s Luck,” one of my favourites, my go-tos, my Munro Lifers. The story is from Who Do You Think You Are?, the saddest, most brutal book I, or anybody else, has ever read. It also happens to be the only Munro story I know of with a major Jewish character (I guess I’m nothing if not predictable…). Rose, the protagonist in every story in the collection, starts an affair with Simon, a Jewish European Holocaust survivor, refugee, and now professor. Feeling herself developing feelings for Simon, terrified of both falling in love and being rejected, Rose gets in her car and abandons her life in Kingston, driving clean across the country. With Rose alternating between this fear and other, softer feelings, Munro writes: “every twenty miles or so, she slowed, even looked for a place to turn around. Then she did not do it, she speeded up, thinking she would drive a little further to make sure her head was clear. Thoughts of herself sitting in the kitchen, images of loss, poured over her again. And so it was, back and forth, as if the rear end of the car was held by a magnetic force, which ebbed and strengthened, ebbed and strengthened again, but the strength was never quite enough to make her turn, and after a while she became almost impersonally curious, seeing it as a real physical force and wondering if it was getting weaker, as she drove, if at some point far ahead the car and she would leap free of it, and she would recognize the moment when she left its field.”

Researching the story, I discover that originally, Simon appeared in a longer, very different story, a story in three parts, each part chronicling another woman’s love affair with Simon. A draft of this story, never published, is in her archives; perhaps one day I will go to Calgary and read it; another discovery. I also discover that Who Do You Think You Are? was originally supposed to contain stories from two different female protagonists, Rose and Janet; it wasn’t until the book was already in proofs that Munro changed it all to Rose, hurrying to Toronto and spending sleepless nights rewriting some Janet stories, removing some, adding others. A stunning last minute change that gave us a stunning whopper of a book. The three Janet stories that didn’t make the cut were included in The Moons of Jupiter. (For more on the material history of Who Do You Think You Are?”, read Helen Hoy’s academic article, “‘Rose and Janet’: Alice Munros’ Metafiction.”)

My father’s mother, who lived her entire life in New York City, was an avid reader of Munro. It’s possible that’s where I first saw her name, on a cheap paperback copy of The Lives of Girls and Women perhaps, sitting on its side on Nana’s haphazard bookshelves, in a house full of haphazard bookshelves.

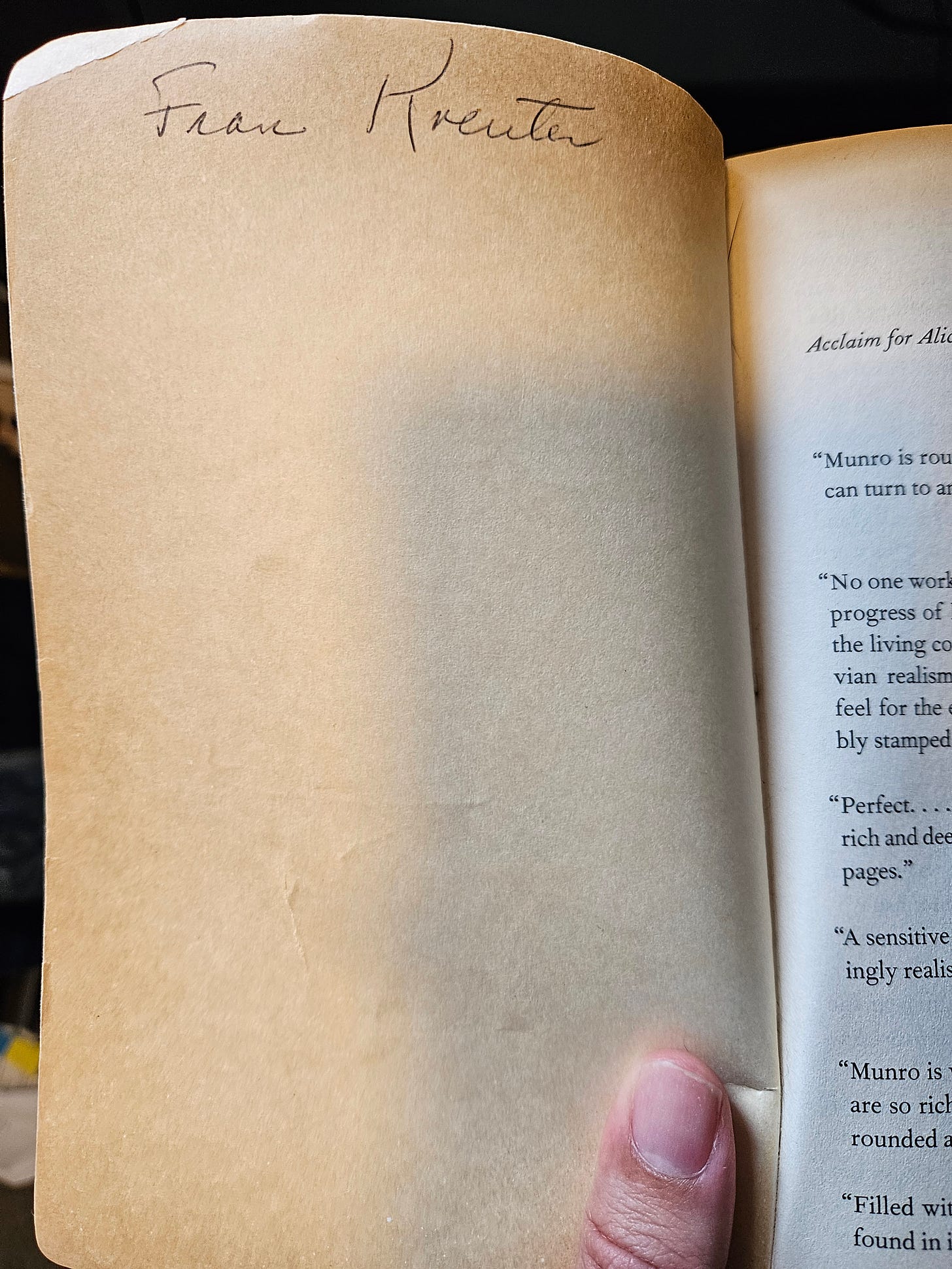

A fair number of the Munros on the shelf above my head as I write this have her signature in it: Fran Kreuter. I open up a hardcover edition of The Love of a Good Woman, find a bookmark from the Salzburger Marionetten Theater. That was my grandmother, travelling the world in old age, collecting pieces of it: but always back to New York, to Queens, to Bayside, to Bell Boulevard.

In the wake of Munro’s death, I’ll be full of the writer’s words, the grandmother’s presence.

The day of Munro’s death, I go to my shelf. The first story that comes into my head is “Miles City, Montana.” I see the two volumes of her selected stories, which I bought at BMV for ten dollars each. I open up the first volume, A Wilderness Station (named after a story never collected in book form before, the reason I bought the selected in the first place), and read her introduction.

In her matter-of-fact way, Munro writes about the moment her writing life took full bloom inside her. Fourteen, looking out the library window of her small town, she sees a team of workhorses having their cargo weighed in the snow.

“This description makes the scene seem as if it was waiting to be painted and hung on the wall to be admired by somebody who has probably never bagged grain,” Munro writes. “The patient horses with their nobly rounded rumps, the humped figure of the driver, the coarse fabric of the sacks. The snow conferring dignity and peace. I didn’t see it framed and removed in that way. I saw it alive and potent, and it gave me something like a blow to the chest. What does this mean, what can be discovered about it, what is the rest of the story? The man and the horses are not symbolic or picturesque, they are moving through a story which is hidden, and now, for a moment, carelessly revealed. How can you get your finger on it, feel that life beating?”

She never will use that image in a story, she claims, but it’s all there, everything she will do in fiction from then on. The life beating.

“Miles City, Montana.” How many unknown times have I read this story? And each time, it opens in me like a slow explosion. The story, in summary, seems simple enough: the narrator and her husband are driving to Toronto from Vancouver with their two young daughters (the reverse trip, I notice for the first time, from Rose escaping a possible future with Simon). The daughters are bright, precocious; the husband seems nice enough, but the way he reacts to there being no lettuce on his sandwich hints at something darker (a few pages later, in a typical Munro time jump, we find out that in the “present” of the story they are indeed divorced). The family stops at the aforementioned Miles City to cool off; there’s a mishap at the swimming pool involving the younger daughter: nothing terrible happens, but something terrible very much almost happened (the story’s frame of the drowning death of a young boy makes this fact sink in). Any number of Munro’s themes are present: morbidity; youth; the distance between Ontario and BC; city life and town life; what one must sacrifice in order to be a mother; the consequences of refusing to make those sacrifices.

One reason I keep returning to this story is its exemplary Munrioian balance of description, narrative, and insight, insight stacked on terrifying insight. On the other end of the story, it’s impossible to not feel changed, altered, wider, more capacious. The only real way to properly quote from a Munro story is to quote the entire story: they are that woven, of the whole, biological. Nonetheless, here’s our first person narrator, confessing her desire for escape from motherhood, from the domestic, the daily: “I wanted to hide so that I could get busy at my real work, which was a sort of wooing of distant parts of myself.” A sentence balanced across a bottomless cave. If a short story by anybody else contained one sentence like this, we would rightly call it a Masterpiece; this story contains dozens of such sentences. And again, this is not unusual for Munro. It is Munro.

After “Miles City, Montana,” I can’t help but read “White Dumps,” the next story in the anthology. And after that, I finally read “A Wilderness Station.” Reading and rereading Munro, a lived life.

As for so many of us, the past seventh months has been focused on Gaza, on horrific scenes of death and destruction and genocide, but also of steadfastness, resolve, hope. It is nice to be reminded, even for a moment, that outside of the horrors of our world there are things like short stories. Life caught in language, in sentences, in paragraphs, narratives spanning abysses.

I have had the privilege of reading Munro’s brilliance while she was alive, of being on the earth concurrently with a mind like hers, a presence that could create fiction like that. And now I join the ranks of everybody for the rest of time, those of us who will have the privilege of reading her after she is gone.